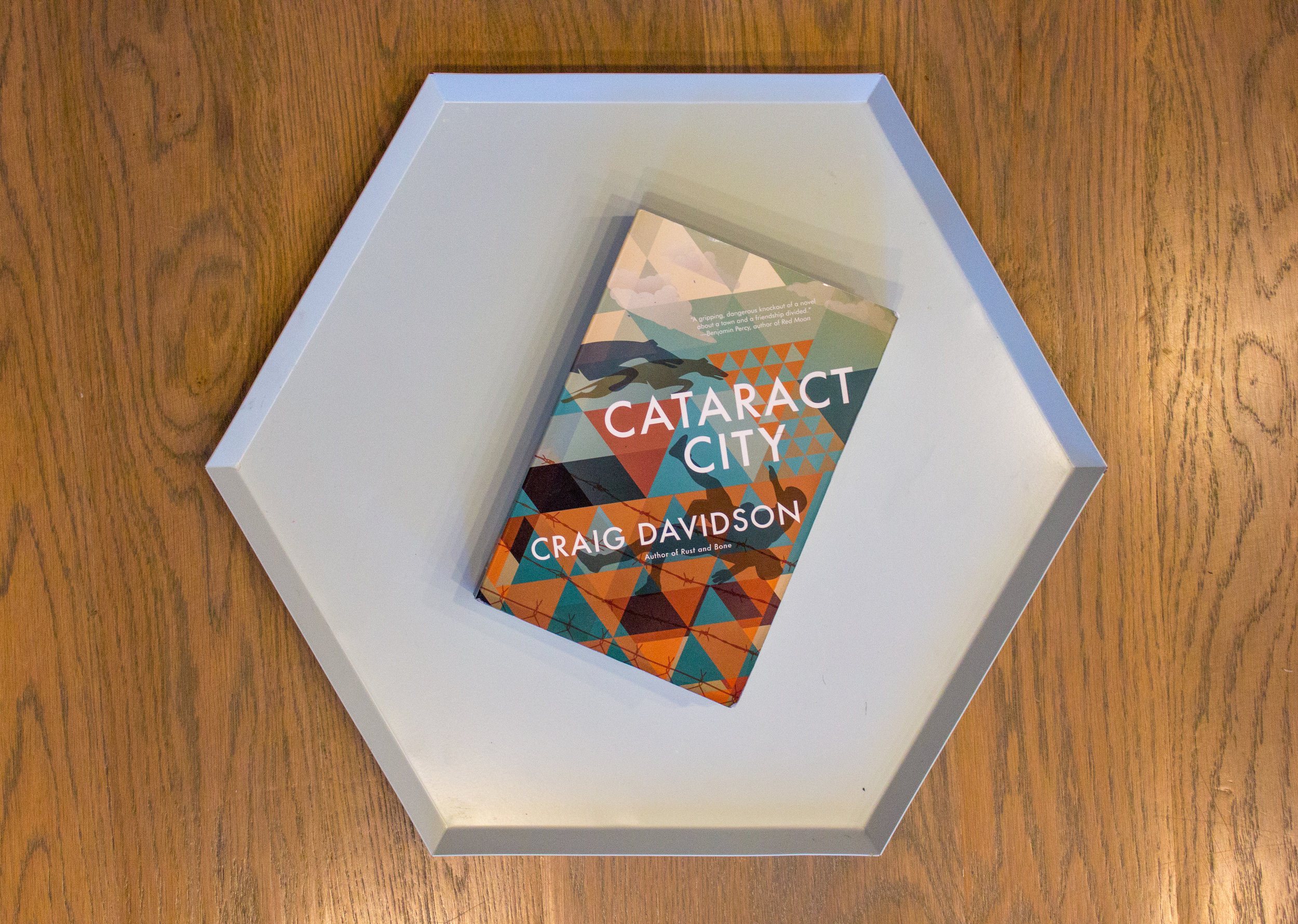

Cataract City

When it comes to books, I’m a serial monogamist. I don’t delight in dabbling – picking one book up, switching to something different, seeing where yet another novel leads. Instead, I tend to read one book at a time, faithfully until it’s done.

Craig Davidson’s Cataract City tested that trait, broke my book-finishing streak, and then proved to me the point of perseverance. It's set in Niagara Falls, and so I began it last December while visiting nearby Niagara-on-the-Lake with my Mom and cousin Nicole. My family trip was charming and calm – all wineries, winter walks, and window-shopping. Cataract City is the inverse – a book detailing Niagara Falls’ underbelly of illegal reserve wrestling, dog racing, and nights at the bar ordering successive rounds of the area’s signature drink combo: a “shot of rye and a Hed.” It was the most aggressively masculine thing I’d ever read, and I barely reached the 100-page mark before abandoning it in favor of Pachinko’s warm embrace.

A week ago, I forced myself to pick up Cataract City again, bracing myself for another interminable slog through the woods with the book’s two protagonists, lifelong friends Owen Stuckey and Duncan Diggs. But while the lost-in-the-woods motif did reappear, my impatience didn’t. Somehow, I managed to get interested in this book about boys, booze, and making bail.

Cataract City isn’t named for a person, an event, or even a mood – it’s named for a town. And that’s an apt choice, because this book is perhaps the purest meditation on place I’ve ever read. Davidson has clearly thought deeply about how the place of your birth forms you, defines you, and can determine who you become. As he writes, “this city makes you; in a million little ways it makes you, and you can’t unmake yourself from it.”

I’ve always thought of Niagara Falls as tiny, tacky, and touristy (if I thought of it at all), but Davidson opened me up to a much more nuanced perspective on the place. He writes beautifully about two characters’ attempts to make sense of the setting they were born into. Below are a bunch of my favorite passages:

“As a kid, I found it tough to get a grip on my hometown’s place in the world. What could I compare it to? New York, Paris, Rome? It wasn’t even a dot on the globe. The nearest city, Toronto, was just a hazy smear across Lake Ontario, downtown skyscrapers like values on a bar graph. I figured most places must be a lot like where I lived: dominated by row houses with tarpaper roofs, squat apartment blocks painted the color of boiled meat, rusted playgrounds, butcher shops, and cramped corner stores where you could buy loose cigarettes for a dime apiece.”

“I saw how a city could sink into you, trapping its pulsing heart inside your own heart – except it never feels like a trap. A trap snags you out of nowhere, violently and without warning. But I know every inch of my trap, didn’t I? I knew the dirt path that led down under the Whirlpool Bridge to a fishing hole stocked with hungry bass. How to jump off the old train trestle in Chippewa and hit the rip of slack water so I could paddle safely to shore. Cataract City was like those fur-covered handcuffs you could get at Tinglers. The city of your birth was the softest trap imaginable. So soft you didn’t even feel how badly you were snared – how could it be a trap when you knew its every spring and tooth?”

“We all occupy our own square of space and time. We have our memories and no one else’s. We live one life, accumulating it in our minds as we go along. The city is part of that too. The city is networked into the memories of everyone who walks those same streets, who works at the same factories, who plays baseball on the same diamonds where the dust still hangs along the base-paths minutes after a player’s passage.”

“My dad said Cataract City is a pressure chamber: living was hard, so boys were forced to become men much faster. That pressure ingrained itself in bodies and faces. You’d see twenty-year-old men whose hands were stained permanently black with grease. Men just past 30 walking with a stoop. Forty year olds with forehead wrinkles as deep as the bark on a redwood. You didn’t age gracefully around here. You just got old.”

Beyond these sweeping stanzas, Cataract City is studded with lovely little bits of language. Davidson describes a bodybuilder as “freakishly muscular, a condom stuffed with walnuts,” captures “the wet, weeping smell of cinderblock walls,” and writes “life in the forest falls like a guillotine blade.”

Ultimately, Cataract City is a book about revenge, about identity, and about the hopes we have for ourselves. In this book, expectations are small, circumstances are hard to overcome, and life is a grind rather than a joy. Physical injury – in the form of smashed noses, ruined limbs, and knuckles worn to the bone from fighting – is inevitable. Working at the ‘Bisk is inevitable. Wishing to escape (but not escaping) is inevitable. This makes Cataract City – both the book and the place – both terribly depressing and wildly interesting. If you can get past the first 100 pages, that is!