Roaming through the Middle East with The Map of Salt and Stars

It’s 2019. Some things haven’t changed – my resolutions are long-abandoned, my completed book count already lags behind my Goodreads goal, and I’m still feverishly finishing novels minutes before our book club meets to discuss them.

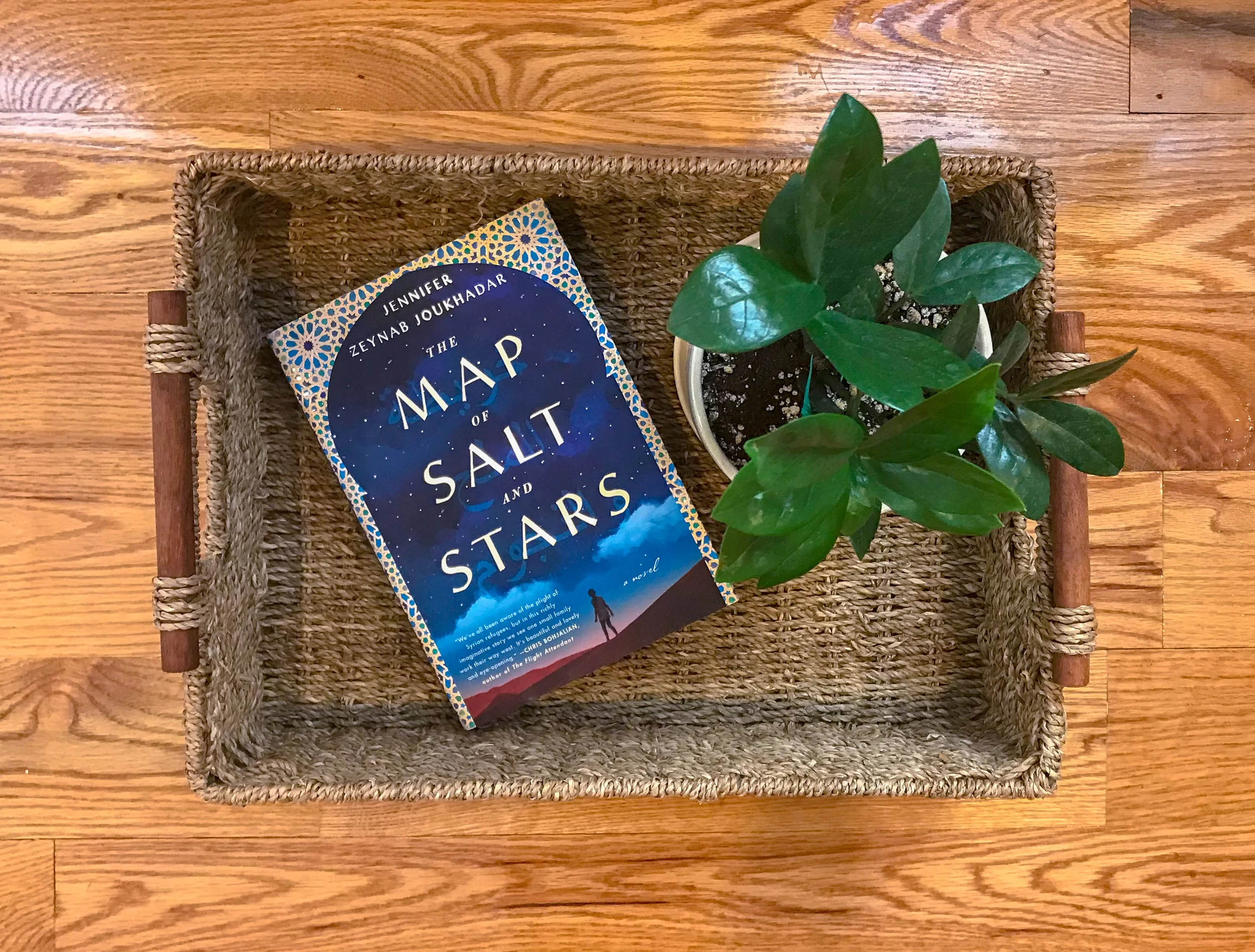

But some things have. I’m now a mother, and apparently therefore also the kind of person who cries when even fictional children are in danger or pain. Which made January’s Vicarious Reading pick – Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar’s The Map of Salt and Stars – a massive minefield. This book had me constantly clutching Kleenex, feigning allergies, and fearing I was just one plot twist away from losing my last shred of stoicism and spending my days sniffling at pictures of puppies and tear-jerking YouTube videos (just try to get through this compilation without sobbing). But I digress.

The Map of Salt and Stars is two stories woven together. The first takes place in the modern-day Middle East. It follows a young girl named Nour who is displaced, along with her mother and sisters, first from America, and then from Syria, Jordan, Egypt, Libya, and Morocco. The second, set 800 years in the past, is the fantastical tale of a girl named Rawiya who disguises herself as a boy in order to travel through the Arab world as a mapmaker’s apprentice.

There are clever parallels here. Both girls are the same age. Both girls pass for boys at various moments. Both girls are preternaturally gifted. Both girls are filled with longing. Both girls endure arduous hardships. And both girls are lucky to come out of it alive.

In Joukhadar’s capable hands, both Nour and Rawiya’s stories burst with lively energy and vivid imagery. Lyrical language abounds, rendering even tragedy and pain poetic. Joukhadar is a master of physical descriptions - she calls the smell of cilantro “prickly” and an old man’s limbs “rice paper hands.” Some of my favorite bits from Nour’s story are below.

Her mother’s tears over her husband’s death:

“That winter, I found salt everywhere - under the coils of the electric burners, between my shoelaces and the envelopes of bills, on the skins of pomegranates in the gold-trimmed fruit bowl.”

Her synesthetic perception of the world:

“Inside, the walls breathe sumac and sigh out the tang of olives. Oil and fat sizzle in a pan, popping up in yellow and black bursts in my ears. The colors of voices and smells tangle in front of me like they’re projected on a screen: the peaks and curves of Huda’s pink-and-purple laugh, the brick-red ping of a kitchen timer, the green bite of baking yeast.”

Her belief that you leave a piece of yourself everywhere you go:

“I lurch and trip and realize I’ve been leaking bits of me all this time. The ghost of me is still scattered across the road from Amman to Aqaba. Shreds of me wander the streets of Homs under the shop awnings. I have no voice, no anchor. How do I keep from ripping apart on the wind like dandelion seeds?”

Her fear of forgetting:

“A broken pipe drips from the cramped apartment building beside me. Is this how people lose themselves, one drop at a time? Memories slide away so quickly – the rooftop garden, the amber-eyed coyote on West 110th, the fig tree in Homs. It would be so easy to forget.”

Joukhadar is also a master of scene-setting. She renders passages with such clarity that they feel cinematic. One moment that really stuck with me when Nour’s family crosses the border from Syria to Jordan but the old storyteller they’re traveling with gets turned away:

““He hobbles after us, a slow, measured walk. He ignores the men shouting at him and stops at the border. He leans on the gate after we’re through, putting his face to the bars. I realize I never asked him his name.

“He has no family to vouch for him,” Mama says.

“Can’t we do anything?”

“He doesn’t have the proper papers,” Mama says. “There is a system. It’s complicated.”

The old storyteller presses his forehead to the bars. He reaches out his hand and flattens his palm against them, his fingertips outstretched. He blinks, slowly, and smiles. His combed black hair reflects the sun, his grey roots a feathered crown. His smile becomes a reminder, a picture to fix in my mind forever.

The sun beats hot on the wild thyme. I trip over my feet on the curb. When I turn back again, the storyteller is still watching us, his words still in my head: It’s living that hurts us.”

In spite of all the lovely language, it’s that hurt that haunts me. There’s so much death in this book. The danger and sadness and sacrifice is unrelenting. Downed boats. Destroyed homes. Bullets at borders. Attempted rapes. Shrapnel and head wounds and fiery fevers. And the stories of everyone Nour loses stirred my imagination in dangerous directions. I see my sweet son’s face in every wrenching story, and can’t help but dwell on how fragile our lives, bodies, and identities are. Hence the need for Kleenex.

But even if you share my compromised new-parent constitution, I promise – this book is a worthy vicarious read. After years of skimming news out of Syria with a mounting sense of numbness, The Map of Salt and Stars rubbed me raw. It was the shot of empathy and understanding I badly needed. And against all odds, Nour’s refugee story and Rawiya’s epic journey each come with happy endings. When Nour made it to Ceuta, I felt my tense, coiled body immediately relax. I cried hot tears, meanwhile, when Rawiya was reunited with her mother and brother. The tears dried powdery-white on my polar-vortexed face, but my sense of wonder remains.